This First Person article is the experience of Ruby Harry, who lives in Vancouver. For more information about CBC's First Person stories, please see the FAQ.

I've spent many years inside correctional institutions, moving from maximum to medium security.

When people talk about justice, they often focus on punishment. But real justice, the kind that heals, is something different.

For me, it began with a process set out in Section 84 of Canada’s Corrections and Conditional Release Act: Release into Indigenous Community. It gave me a reason to believe that coming home was possible.

Tl’etinqox t’in will always be home to me. I was raised in culture by my grandparents near Williams Lake, B.C. My granny was a powerful medicine woman whom I saw heal people through her work. As a community, we were often in ceremony and there was sobriety in that space.

My grandparents died when I was a teenager and I drifted from their teachings as unhealthy coping took hold. I stayed sober through the years raising my children, but I lost my grounding in culture. I carried the intergenerational trauma from my family’s time in residential schools and my own experience in day school, where abuse and secrecy led to my deep dissociation.

Harry, pictured as a Grade 1 student, at Anaham Day School in Tl'etinqox. (Submitted by Ruby Harry)

Harry, pictured as a Grade 1 student, at Anaham Day School in Tl'etinqox. (Submitted by Ruby Harry)Over time, I became disconnected from the guidance I was raised with. When I was incarcerated between 1997 and 2018, that absence of culture became even more apparent. I instinctively knew from my memories of my grandmother that I could not heal without it.

I was at Surrey Pretrial Services Centre when I found a donated, dusty drum sitting unused and covered in dust. To me, that felt so disrespectful because the drum carries a spirit of its own.

I cleaned it and placed it where it could be honoured, but I didn’t play it. Cultural practice from my community meant I had to stand behind it for a year — to learn from it, to listen and to show respect before I was ready to bring its voice back. When I was finally ready to drum, it felt like the spirit of that drum was drumming me, too. It reminded me who I was and where I came from.

After that, I requested a traditional vision quest — four days of fasting and prayer for guidance — which had to be arranged through an elder and an outside facilitator.

From there, I kept looking and asking for more access to culture and ceremony. I shared my Tsilhqot’in language with anyone who wanted to learn, teaching simple greetings and phrases. I also began reviving drumming and ceremonies. Some of the women who were in there with me had never experienced any of it before so we helped each other remember who we were.

Turning my pain into purpose did not happen overnight. I saw people around me carrying the same pain I did and I told them, “I’ll help you, you help me, let’s help each other.” That small act of mutual care became the start of something bigger.

Near the end of my sentence, while at the Fraser Valley Institution for Women, I learned about Section 84 from other women inside. Section 84 gives Indigenous people in federal custody the right to plan their release in an urban community in partnership with an Indigenous organization. For me, it was more than a legal process; it was a turning point.

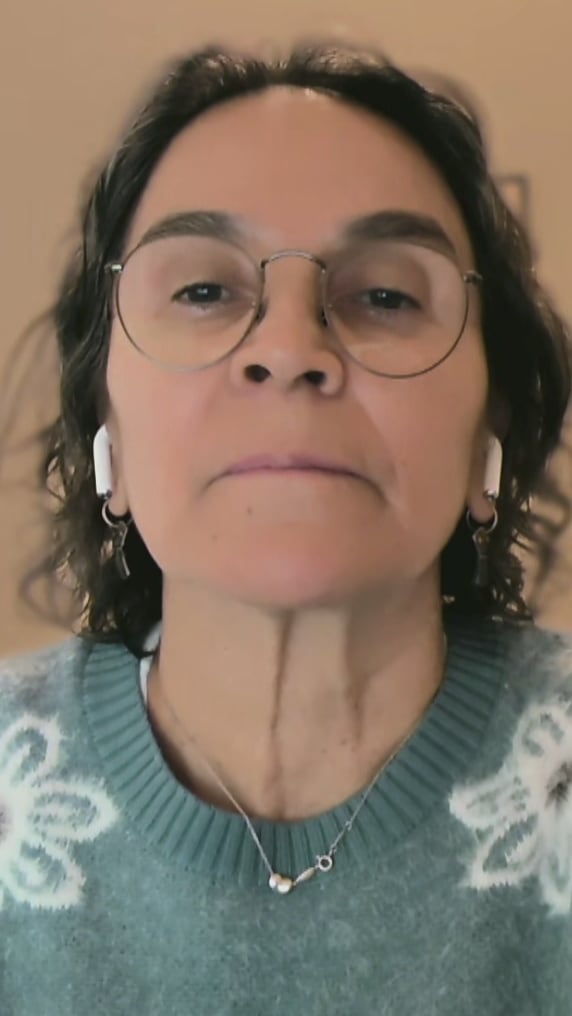

WATCH | An alternative path to healing:The National's Paul Hunter asks Marlee Liss, founder of the advocacy group Survivors for Justice Reform and a sexual assault survivor, to explain why she believes restorative justice offers an alternative path to healing.It resonated with me because I had drifted away from the teachings of my grandparents and elders, and this law felt like a way to come back to those teachings. I just needed a fresh start somewhere focused on healing and opportunity. So I began researching, asking questions and drafting the paperwork all by myself.

In 2018, I was released to the Anderson Lodge Healing Centre for Women in Vancouver, which is run by the Circle of Eagles Lodge Society in Vancouver.

After being released to the Anderson Lodge Healing Centre for Women in Vancouver, which is run by the Circle of Eagles Lodge Society, Harry had access to ceremony like drumming and began working in construction in 2019. (Submitted by Ruby Harry)

After being released to the Anderson Lodge Healing Centre for Women in Vancouver, which is run by the Circle of Eagles Lodge Society, Harry had access to ceremony like drumming and began working in construction in 2019. (Submitted by Ruby Harry)I had my own room and access to ceremony like sweats and drumming. Staff were there day and night if I needed support. With the encouragement of elders and the staff, I started making blankets again — just like how my granny taught me to sew — and turned my craft into a way to earn income.

That's how I launched my business, Ruby’s Star Blankets, while living at Anderson Lodge, first sewing on the kitchen floor and then eventually getting my own workroom.

That support of culture and ceremony gave me direction and showed me that healing can also build independence — something that had never happened in past releases.

Before, I always had to search for culture on my own. At Anderson Lodge, developing life and job skills was part of daily life along with ceremonies, teachings and elders.

During that time, I also began working in construction, learning metal fabrication and earning my construction safety officer and first aid certifications. Later, I joined the Phil Bouvier Family Centre, where I have held various roles and still work today supporting Indigenous parents and children through ceremony.

While at Phil Bouvier, I started a catering company, which continued to grow and eventually became Medicine Wheels, a catering food truck serving fusion dishes such as bison chili, elk stew and my grandmother’s bannock.

Food brings people together in ways that words cannot, letting me share that sense of connection and remind others that it is its own kind of medicine.

Left: Harry started Medicine Wheels, a Indigenous fusion food truck, earlier this year. Right: Harry was awarded the King Charles III Coronation Medal in June 2025. From left to right: Sen. Kim Pate, Bren Hurst, Harry, Greg Peters. (Submitted by Ruby Harry)

Left: Harry started Medicine Wheels, a Indigenous fusion food truck, earlier this year. Right: Harry was awarded the King Charles III Coronation Medal in June 2025. From left to right: Sen. Kim Pate, Bren Hurst, Harry, Greg Peters. (Submitted by Ruby Harry)Every role I have — mother, worker, elder, business owner — is now grounded in culture and the teachings that helped me come home the right way through Section 84. This year, that journey was recognized in Ottawa when I received the King Charles III Coronation Medal for outstanding achievements that make a difference in Canada and in communities.

I know first-hand that restorative justice can work. It takes effort and honesty. It's not a free pass. You do not just walk out of prison and into a halfway house. Before leaving federal custody, I had twice the counselling, twice the therapy programs and twice the work to earn that freedom compared to previous releases. By the time I was ready to leave, I felt like I really understood what community means and what safety really feels like.

My journey is not unique. There are many others like me who only need a way back that includes culture and compassion. That is what Section 84 and groups like Circle of Eagles offer: not shortcuts, but second chances rooted in accountability and belonging.

Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Here's more info on how to pitch to us.