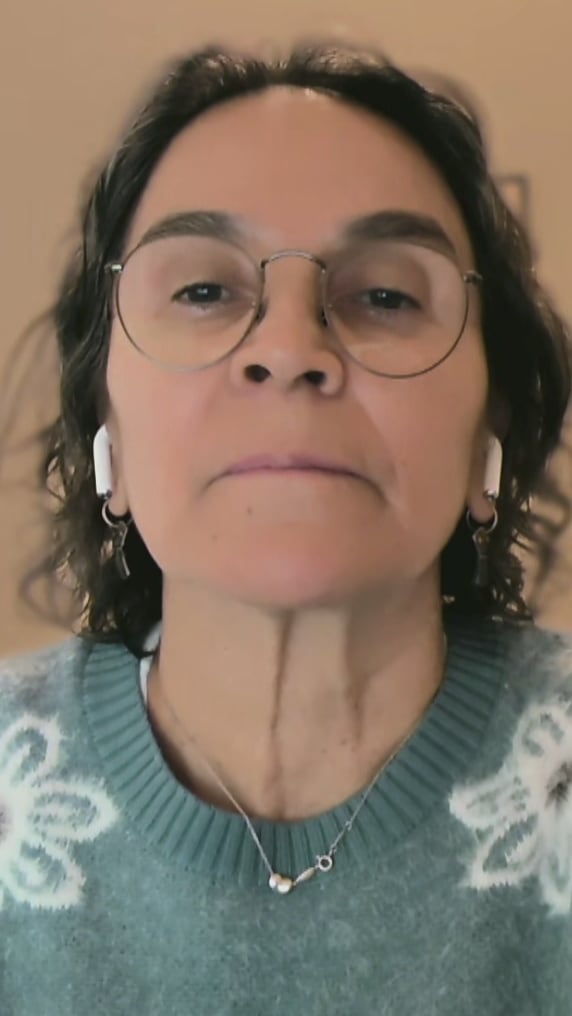

In a quiet room in the University of New Brunswick's library, Ramona Nicholas gives a small laugh when asked what it's like to be part of an archeological project involving her ancestors.

"I wanna say, it's about time," said Nicholas, the Wabanaki Heritage Lead at the University of New Brunswick.

Nicholas is one of the co-leads in this project, a collaboration between university researchers and the Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick.

Their shared goal lies in the plain banker-style boxes housed in the university's Archives and Special Collections Department. Each one is labelled "Bailey Indian Artifact Collection," and contains a rich history of Wabanaki heritage. While the contents of these boxes were collected in the late 19th and early 20th century, they've never before been thoroughly studied or even catalogued.

Until a few years ago, the Wolastoqey Nation didn't even know most of it existed.

LISTEN | Hear the voices sifting through the artifacts:Atlantic Voice26:10The Artifacts of Our Ancestors

A rich collection of Indigenous artifacts sat untouched for decades on the University of New Brunswick's campus. When archeologists began opening up the boxes, what they found sparked a collaboration with the Wolastoqey Nation, and has opened up new windows to the past, and new ways forward. Listen to the voices involved in this project in a new documentary from Myfanwy Davies.Neither did a few archeologists, who began poking around at the collection in 2023, as part of a separate research project. What they thought were perhaps 25 artifacts total in the Bailey collection — turned out to be 25 boxes.

"Immediately, the scope of this kind of grew, and we were like, 'oh, wow, that's pretty significant,'" said Ken Holyoke, another of the project's co-leads and assistant professor of archeology at the University of Lethbridge.

19th century originsThe archeologists weren't entirely surprised there were more objects than initially thought.

The titular Bailey of the collection is Loring Woart Bailey, a scientist and long-time professor at the University of New Brunswick, teaching from 1861 to 1907. A side interest of his was collecting artifacts, most from along the Wolostoq or in and around Maquapit Lake, some of which he displayed in an on-campus museum at the time.

Some of the catalogued artifacts from the Bailey Collection. (Chad Ingraham/CBC)

Some of the catalogued artifacts from the Bailey Collection. (Chad Ingraham/CBC)"The work that Bailey did wouldn't be what we would call archaeology," said Holyoke. "In fact, a lot of what he did was, you know, really would be considered looting by today's standards."

Bailey collected objects without consent, said Holyoke, and in doing so disturbed archeological sites, removing belongings from their context. That context — where the object was found, what it was near, and other factors — is a key tool archeologists use to understand the past.

"Folks... who were out there collecting at the time, were sort of collecting indiscriminately," said project co-lead Trevor Dow, who also teaches archeology at UNB. "They didn't really seem to give much thought, or care, to where they were collecting from."

As Dow began opening up the boxes, the trove that lay inside prompted an idea. Dow found objects associated with burials, including some beads that — according to Bailey's notes — came from the burial of a child in the Tobique region.

"We hit pause immediately," said Holyoke.

"And the first thing we could think of was that we should reach out to the Wolastoqey Nation to get guidance. First of all, to inform them about the collection, if they didn't already know about it, and then try to figure out what we could do moving forward."

Ceremony and changeThe Wolastoqey Nation had only a small inkling of what lay in the archives. Years before, Ramona Nicholas, who was Elder-in-Residence at UNB at that time, had performed ceremony around those burial-related beads.

"I don't want to say it felt good, but there was a good feeling about being able to bring some ceremony to that," said Nicholas.

From there, the archeologists and First Nation set up a meeting to figure out how to move forward. The collection was made accessible to Wolastoqey members for visits, community meetings were held, and Wolastoqey students were brought on board with the research work of documenting and cataloguing the artifacts.

"This became this opportunity to be like, wow, we can tell these stories," said Jamie Gorman, the resource development consultation coordinator with Neqotkuk First Nation. "We could do 3D casting... we could do a tour in the communities and expose people to these objects."

This groundstone frog sculpture in the Bailey Collection is considered a "one-of-a-kind object," by archeologist Trevor Dow. (Chad Ingraham/CBC)'We were always here'

This groundstone frog sculpture in the Bailey Collection is considered a "one-of-a-kind object," by archeologist Trevor Dow. (Chad Ingraham/CBC)'We were always here'The research team has inventoried and measured boxes' worth of objects — setting aside sensitive burial materials to let elders and other Wolastoqey leaders decide the best way to document them, or not.

Some objects, like groundstone axes, date back to the Late Paleoindian Period between 11,000 and 9,500 years ago — a time when, previously thought, there was little evidence of human activity in New Brunswick.

"See, we were always here," said Nicholas.

While there's more inventory work to be done, what has been completed thus far opens a window into ancestral life, particularly during two later time periods that haven't been well understood in the Maritimes — the Late Maritime Archaic Period and the Early Maritime Woodland period.

"This collection is significant in the sense that we can learn a lot about a very limited time frame," said Holyoke.

Amid the beads, projectile points and tools, one item that stands out to the researchers is a small stone sculpture of a frog.

"It is wholly unique. We never really see artifacts like this in the archaeological record," said Dow.

"There's not many collections sort of as big as this, and as spectacular," said Dallas Tomah, a research assistant, UNB student and member of Wotstak First Nation, also known as Woodstock First Nation.

The collection brings up mixed feelings for Tomah.

"There's a sort of bittersweet-ness to it," he said. On one hand, Tomah said he's amazed at the craft of his predecessors. But on the other, there's a sense of sadness that these types of collections are often largely inaccessible to their Indigenous descendants.

A glass bead, likely manufactured in Europe, found in the Bailey Collection. (Chad Ingraham/CBC)

A glass bead, likely manufactured in Europe, found in the Bailey Collection. (Chad Ingraham/CBC)"This is a very small fraction of what Indigenous communities don't have access to," Tomah said.

"And I think it's a really important problem that we need to address, and need to ensure, that Indigenous communities are involved and aware of where their heritage is."

Holyoke agreed that this current project can become a case study for opening up other archeological collections, respectful practices, and "allow communities to make decisions about the kinds of research that's being done on their pasts — and who is doing that research."

Tomah, Nicholas and others want to ultimately see the collection returned to the First Nation.

"I think it would be an incredible healing process for Indigenous communities to have access to these materials, and be able to determine, sort of what happens to them further in the future," said Tomah.

Holyoke said there been preliminary talks toward that, and those will continue as the group figures out the best path forward, with ideas being tossed around that include bringing the items on a road show of sorts to the community.

This project, and the collection itself, is also currently in the process of getting a new name — Nicholas recently led a talking circle toward that end, one of a series of talking circles and community meetings to continue expanding access to the artifacts.

To Gorman, while the collection does open up uncomfortable conversations about history, the fact that Wolastoqey voices are integrated into this project is a step in the right direction.

"This is a good news story, more than it is emblematic of injustice in the past," he said.